Grandpa is not doing well. My mom said this to me two days before I joined both my parents for a 900-mile road trip. A trip to say goodbye to my best friend.

We drove from Colorado Springs, Colorado, to Peru, Illinois, where my grandfather lay dying in a hospital. It was too late to do the things we used to do together. Too late to sit and talk, watch a movie, or play cards. But I hoped it wasn’t too late to see him one last time.

It was April 2005 and Keith Lowery was 93, but days earlier, he’d suffered an internal rip in his stomach. The pain caused him to pass out and collapse in his kitchen; the fall resulted in a neck injury. Thankfully, a neighbor found him and called for help or he may have died there.

The hole in his stomach and the neck injury both required surgery. Doctors felt that, at his age, he might survive one surgery, but it was unlikely he’d make it through both.

I’d had existing plans to join my parents on a trip to visit him in May, but in mid-April, I received word of his health problems. My initial instinct was to book the first flight I could to Chicago, but optimistic relatives talked me out of it, saying they believed he’d make a full recovery.

He didn’t. He worsened, quickly. So I set out on a trip to say goodbye, if he could make it that long. One thought kept circling my mind: Just hang on. It seems selfish now. He must have been in a tremendous amount of pain, but silently, I was pleading with him to hang on long enough for me to get to Illinois.

My dad drove the majority of the way as I watched the barren plains of Colorado pass outside the window. Just hang on, I thought. Then we passed the cornfields of Nebraska. C’mon, just hang on.

We stopped in Lincoln, Nebraska, for the night. I’d have preferred to just keep driving through the night, and if I’d been traveling solo, I probably would have.

I was unable to sleep. I paced the floor of my hotel room for a while before giving up and going to the lobby with my laptop. I spent the evening writing, reading the local newspaper, and chatting with temporary friends I’d made: the woman working the front desk; a guy who’d clearly been out partying all night and, at 3 a.m., stumbled in to eat a waffle; a business traveler who emerged from her room around 6 a.m. to send some emails while eating breakfast.

My parents eventually awoke and we hit the road again. We were still 400 miles away, but in a few hours, I’d be at my grandfather’s side. If he could just hang on, I could at least say goodbye.

Family members in Illinois told him we were on our way, and thankfully, he held on; he wanted to say goodbye too, apparently. He was awake when we arrived, but unable to speak. Tears formed in his eyes, a small sign that gave me confirmation he knew we were there.

It was the last time he was conscious though. For the next 40-or-so hours, I sat at his bedside with my cousin Celeste on his other side. My mom called us “the bookends.” We told stories, to him and to each other. Leaning over in our chairs, we slept a little when we could, our heads resting beside him.

Some time on day two, my mom convinced us to take a break, and we went to a nearby gas station for some non-hospital coffee. Sleep deprived and suddenly unfamiliar with the outside world, we struggled to get the coffee machine to grind beans and produce coffee. Though the gas station attendant likely thought we were high on something illegal, it was simply the effects of pure exhaustion and the uncontrollable laughter that accompanies it. It was the most we’d laughed in days.

It was a needed break. A necessary distraction. But we soon returned to our posts, and late that evening, we both drifted off beside him once again, soothed to sleep by the rhythm of his breaths.

Something changed in the early morning hours though. His breathing became shallow and strained. It woke both of us around 4 a.m. We looked at each other from opposite sides of our grandfather’s bed without saying a word. We knew it was the end.

I hurried to the waiting room to tell my dad what was happening. I said few words and he said none. He wiped the sleep from his eyes and followed me back to Grandpa’s room.

Dad took up a position at the foot of the bed and I returned to my spot, opposite my fellow bookend. We again told stories. We shared memories. And we tried to let Grandpa know he was loved.

We watched his chest rise and fall with each breath. Then we watched him inhale one last time. I remember glancing up at the clock on the wall. It was 5 a.m. on the spot.

At some point, I wandered down the hall and out the ER doors. The morning air was cool and still. The sky was a beautiful mix of dark blue and orange. Birds were chirping loudly. So many of them singing the song of the morning. I remember this best.

Celeste was sitting on a bench. I sat down next to her and we shared more stories. Stories of his humor, his love, and his life.

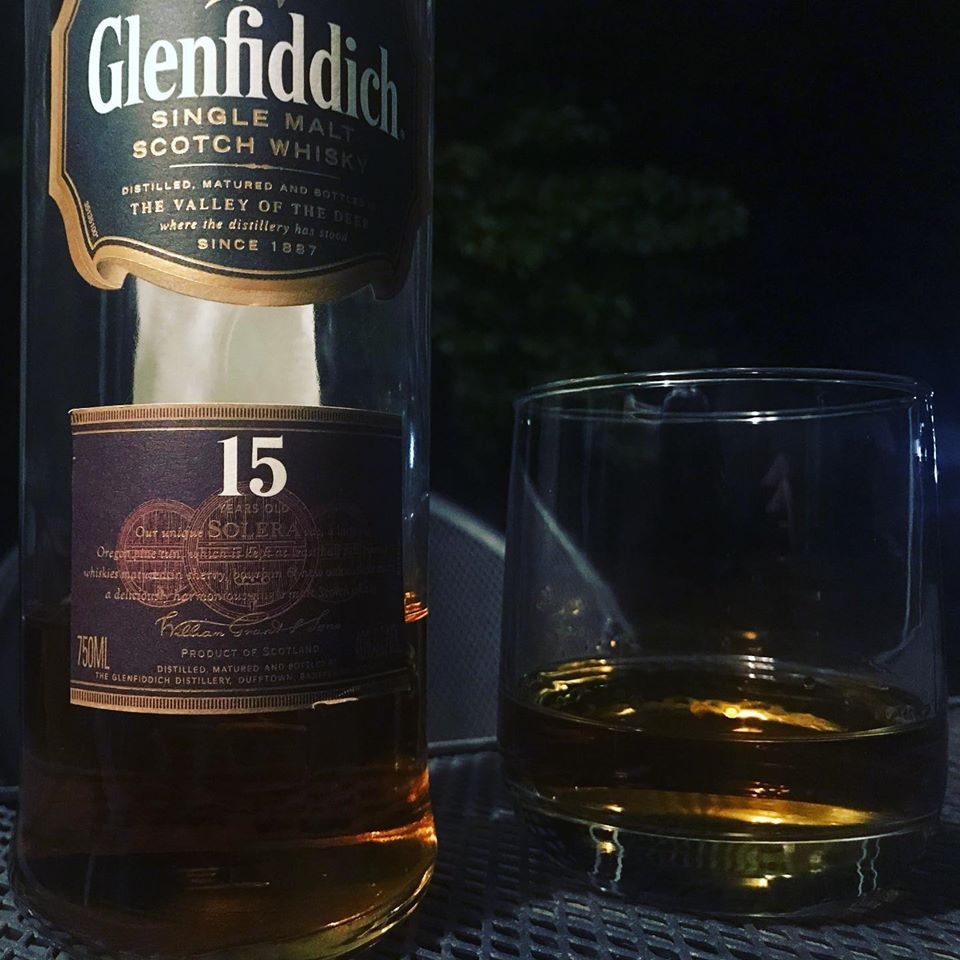

To this day, even 15 years later, I still pause at 5 a.m. Central time on April 30 to reminisce about his humor, his love, his life. To salute him, and for a few minutes each year, I feel like I’m with him once again.

This year’s toast came amid the coronavirus pandemic. At least 51,000 Americans have died from COVID-19 as of April 30. The vast majority of those who died did so without family by their side, and the family members who wanted to be with their loved one were not allowed inside hospitals. As much as I miss my friend, I am even more thankful that I got to see him one last time, and that I was able to say goodbye.